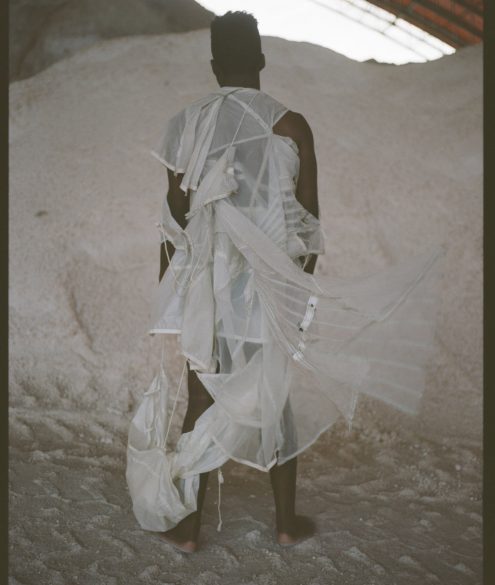

Elena Velez is a recent Parsons graduate, whose collection _andcarryon caught the attention of artists around the world. She has since been featured in Paper Magazine, Dazed, i-D, BOF, Vogue, and more. art+misfits caught up with Elena to discuss her ingenious design perspective and process, as well as her journey so far and where she hopes to go in the future.

1. How would you describe yourself as an artist?

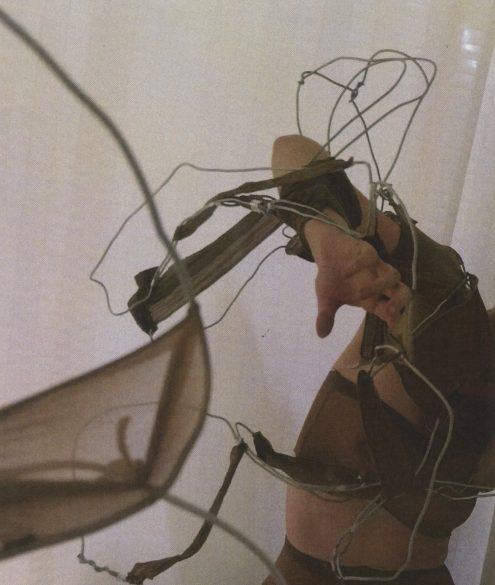

EV: My recent work examines the resilience of post-apocalyptic, industrial restoration. Rebuilding post-war, doomsday preppers.. people who start from square one. I’m really Inspired by what I like to call “Aftermath Industries”, which are scenarios that I think highlight the ingenuity of creativity under constraint. I like to examine parallels and potential solutions to contemporary industrial pressures by way of precedents set throughout history and subculture.

I try to approach conceptual fashion design through a fine art lens, placing authenticity of process before aesthetic: reflection above result. Designers have a unique opportunity to be creative problem solvers. One day I’d like to operate a label that rejects the current conventions of excess, fast fashion, and ecological disregard while stressing quality of design, functional longevity, and compelling storytelling as ultimate remedy.

One day I’d like to operate a label that rejects the current conventions of excess, fast fashion, and ecological disregard while stressing quality of design, functional longevity, and compelling storytelling as ultimate remedy.

What is your design process like? Where do you pull inspiration from?

EV: My design process starts off pretty academically. I’m a really linear-operating person and I like to first start by compartmentalizing different forms of research and starting to build a narrative from the most successful elements. I start a collection the same way I draft a research paper. I start by creating a thesis statement, or a short paragraph on my intentions for the project and then I begin to develop through different types of research. I put my concept through primary research (research that comes from my own mind i.e. paintings, photographs, recordings, sketches, journaling), and then secondary research (research that I obtain from a different source i.e. interviews, literature, newspapers). From this body of content, I can start to sculpt my favorite bits into a narrative that informs the designs that result.

Your collection _and carry on was inspired by the “1941 wartime utility garment industry.” What drew you to such a concept? Although it’s reminiscing on a previous time period, do you feel as if the ideas and themes behind your collection still apply to our world today?

EV: Absolutely – the point of my thesis project was to identify and replicate the most successful techniques of that era. I’ve always been really inspired by mankind and our ability to both create and destroy. That was the starting point of my thesis. WWII was a case study that illustrated that idea the strongest to me. I was inspired by the horrible beauty of war-torn architecture but also so intrigued by the genius industrial renovation that was taking place at the same time. I saw parallels to the issues they were seeking to rectify back then, today: dwindling resources, the loss of domestic labor, the need for recycling and prolonging the lifespan of a garment… It’s also my way of honoring the hard-earned skills and techniques that were afforded to humanity by our ancestors through serious hardship. We have lots of answers to address the issues of today if we look to the past. I suppose that’s the ultimate statement I wanted to get across.

What do you feel are the most difficult aspect of being a designer, and how do you overcome those struggles?

EV: It can be a very competitive and insecure industry to work in if you spend too much time looking over the shoulders of your peers. If I stopped to think about the impossibility or improbability of what I’m trying to do – become a fashion designer in New York City with no money, no business experience, no network connections – I would be crippled with discouragement. So I don’t. I operate as a world unto myself, I aim to please the people who identify with my product and at the end of the day I’m content that I’ve created something wholly original that people either like or don’t. Approval isn’t really something that would change my need to create. I keep that healthy mindset by treating my career in fashion like a marathon not a race. I don’t need to finish first, it’s just a privilege and a blast to run. It can also be very vulnerable to put a piece of yourself into the world like we do. Not everyone will respond to it well. People on the internet are really mean. It helps to have a sense of humor about those sorts of things.

It’s important to me to offer something of merit to the industry and not to enjoy a comfortable yet self-congratulatory career as someone who simply makes pretty things for rich people.

On the other hand, what have been the greatest aspects of your artistic journey?

EV: The ability to create a universe and to tell a story. To leave behind something tangible and beautiful that would never exist if I myself, or the factors in my life that make me who I am, existed. To use my talent and my passion for good in an industry in need of serious repair, as well as a tool for critical commentary on the world I live in. Its an outlet for me to apply life skills that fulfill me – entrepreneurship, meditation, craft making, self-reflection, community engagement, multidisciplinary collaboration – I could go on forever…

What are your thoughts on where the fashion industry is at the moment? Is there anything that you hope to change?

EV: The sustainability component of my brand is not a sales pitch or a special feature. It’s an essential and non-negotiable reality of creating a product in the world today. Treating the conversation on conservation and sustainability like a trend is irresponsible and out of touch with reality. What I’d like to do with my brand is to continue to interpret sustainably ingenious techniques applied during other aftermath industries into design for today and tomorrow. I imagine each collection as a discovery of a new bank of techniques that roll over into the next season and ultimately become the codes of my brand. Each body of work is a progressive culmination of its predecessors, evolving and expanding as my brand grows. It’s important to me to offer something of merit to the industry and not to enjoy a comfortable yet self-congratulatory career as someone who simply makes pretty things for rich people.

On that note, what do you hope to contribute to the fashion industry, or the world, as an emerging designer?

EV: Maybe a technique or a trend that leads to a small change in how we make or design things. Maybe a piece that sparks a conversation that leads to a new friendship. Maybe a thing that makes someone challenge themselves to think about something differently. I think that there is equal beauty in the tiny interactions and outward vibrations that occur when something new is manifested. I just want those vibrations to be positive, responsible, and progressive.

What advice would you have to give to young designers or artists?

EV: Get to know yourself. Learn the vocabulary to articulate the things that interest you- you’ll be doing those the most. Don’t compare yourself to anyone with resources that you know you haven’t got. Know that you have everything you need to be successful at this very moment. There isn’t a question you can’t google, a tutorial you can’t youtube, a potential mentor you can’t email. There’s a homeless man in Union Square park who makes the most gorgeous garments with trash and love. Drop the excuses and get back to work.